Over Some Humps

By Scott Kruize

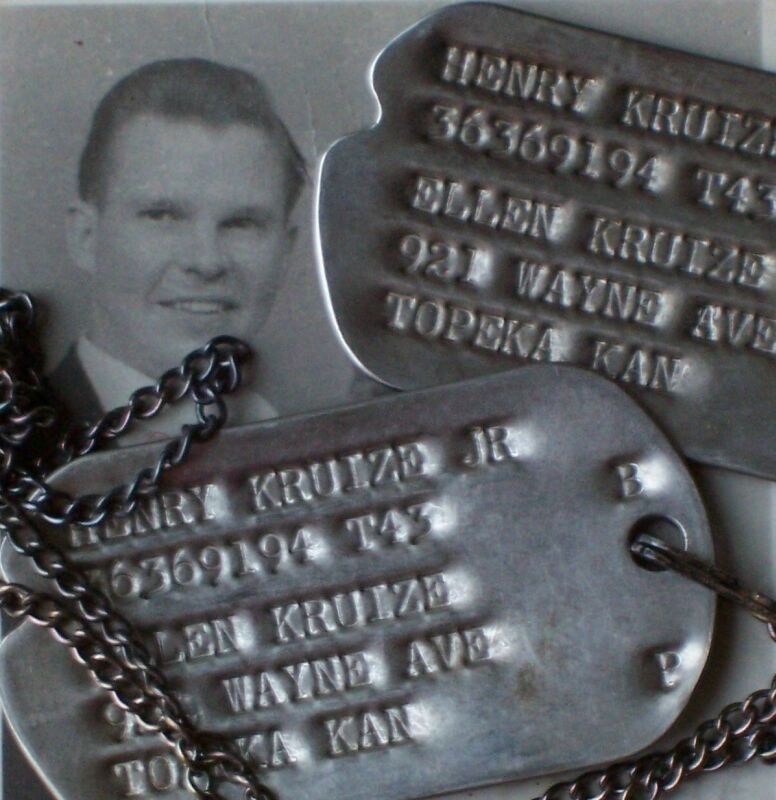

A book I originally purchased, plus some other artifacts that I’ve known all my life, have recently come into my permanent possession. Indulge me as I make at least some connection to ‘Modeling Now and Then’…

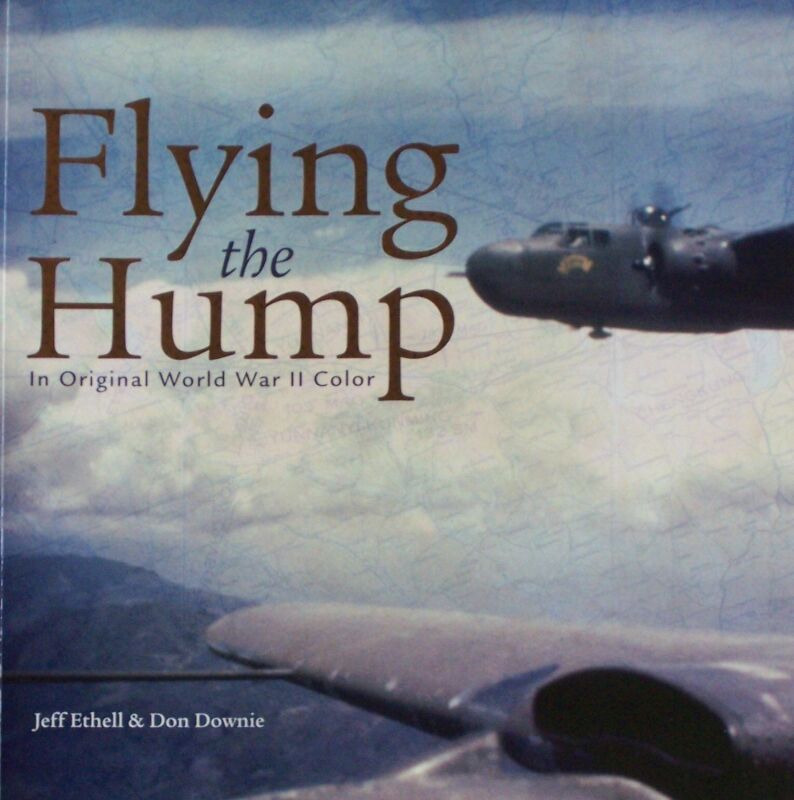

The book is Flying the Hump (In Original World War II Color), by Jeffrey Ethel and Don Downie. (Copyright 1995 and 2004, by MBI Motorbooks; paperback, 168 pages.) Our impression, for decades, was that WWII was fought in black-and-white, based on textbooks and newsreel footage. But Kodachrome came out in 1935, in 16mm movie reels and in 35mm cassettes to fit the ‘new’ miniature cameras of the era, and during the war, many of the 11 million former civilians who served with the American military carried their cameras, some loaded with Kodachrome, to the far corners of the world. "Kilroy Was Here", as we all know. Mr. Ethel and others have been coaxing these movies and slides from Kilroy’s closets, where they’ve lain obscurely for decades, and this book is one of the results.

Since I started modeling at age 11, I've taken in all kinds of subjects: First World War fighters, modern jets, the starship Enterprise while the first TV series was running, and even old Pyro horse-drawn, Dalmatian-escorted firefighting wagons from before the turn of the prior century. But warplanes from the Second World War have taken most of my time and effort, for a variety of reasons. The sheer variety, in types and liveries, as the numbers of planes, and the sizes of air forces from that seven-year slice of history, dwarf anything before or since. The interesting technological perspective: the beginning of the war saw what seemed like only slightly-refined WWI-like fighter biplanes, the middle the absolute peak of high-performance piston-powered monoplanes, the end introducing jets and rockets that pointed to the future. But mainly the cool color schemes: camouflaged war paint set off with a wide variety of national insignia!

There's another reason. World War II seems particularly real to me, and building replicas of its important artifacts is particularly satisfying. I wasn’t in that war –for which I’m eternally grateful—but my father was.

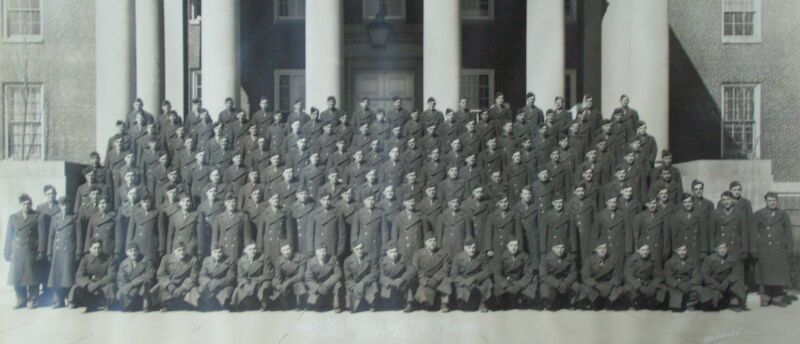

He enlisted in 1942. Not in any furious bloodlust for combat, but because his lifelong philosophy was "Do what has to be done." Reading accounts of veterans, and listening to them at Pierce College's ‘World War II Week’, gives the impression that most American servicemen were like my father in this. They were clueless, innocent ‘homeboys’ when they signed up. Most hadn’t previously been anywhere, done much, or known anything. They certainly started out knowing nothing of war, and weren’t ‘warriors’ in any recognizable classic definition of the term. They just wanted to do their bits to get the war won and go home again…which they did…and in the process, we note, thoroughly stomped the professional and fanatically devoted ‘warriors’ of the enemy…

Father was bright and had already accumulated some time in college, so when he joined the army, they put him into technical training: radio communications for the Army Air Force. He hadn't previously known anything about radio, but studied hard and well, was given the rank of Staff Sergeant, and sent to the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations.

Anyone who’s heard of this theater, enough to have noted the lack of spectacular allied advances and victories, would do well to read the book Flying the Hump. Providing the means for the Allies to maintain even the small forces there, and other military resources to help the Chinese, so far back in the mountainous interior, meant flying everything from India over ‘the Hump’: the Himalayan mountains. It was very difficult and expensive. The India Transport Command (the China wing of the U. S. Army’s Air Transport Command) lost some 600 aircraft during the war, few to enemy action. Most were wrecked in the hazardous terrain, trying to fly over it through its vile weather.

Father himself made the trip safely, but once at his base, assigned to duty on the radio, he sometimes took distress calls, and had to listen to the voices of men going down to their doom. He never mentioned this to me, but told all to my mother during courtship when he returned from the war, and more recently told my brother James about it, while he was ailing.

There were other ‘humps’. Father did tell me about Imperial Japanese Army aircraft dropping bombs on his head, fortunately not quite closely enough. (Hence my existence!)

Japan surrendered, a major ‘hump’ for him and the other servicemen that occurred much sooner than they’d expected, due to that surprising, terrible superweapon. He had to stay on a few months, nervously guarding American military assets, while the Kuomintang and Communists resumed their internal conflict for control of China. On guard duty, he’d contemplate how little he wanted to be killed in an ‘incident’ after having survived the huge war against the Axis.

That didn’t happen, and of course he was eventually released and sent home, completing a trip around the world at Uncle Sam's expense. Back in the States, he finished his college education, married my mother, and provided for me and three siblings.

So I always thought modeling World War II subjects was cool. When Dad’s parents gave me God Is My Co-Pilot, and the Idlewild School Library had 30 Seconds Over Tokyo, of course I had to build Monogram’s old ‘Forty-Niner’ P-40. Father recalled meeting General Claire Chennault; how cool is that! I was also excited to recognize a tentative connection between Dad’s service and the Hawker Hurricane, my favorite WWII fighter. He never saw any in northern China, but Hurricanes fought to the south of him in Burma, alongside the Flying Tigers and later the 14th Air Force, and had been the primary aerial guards of India as he passed through it.

Dad was never garrulous, but did mention seeing Mustangs at Chinese air bases, later in the war as the P-40s wore out. I’d thought of them only in the European context, guarding the 8th Air Force bomber fleets, but they did serve in China with the 14th Air Force, and (sure enough!) Flying the Hump has a color shot of several, warlike in their olive drab paint, set off by white identification stripes along the aft fuselages and tails. This book is a great boon to modelers who want to accurately reproduce the aircraft and other equipment in service in the CBI.

I bought the book a couple of years ago at a vendor’s table at southern California air show. I visit my brother Chris in L.A. every year so, and he takes me to air shows, often larger than any in the Pacific Northwest. We enjoyed looking it over, and Father was grateful for the gift when I brought it home.

It added to artifacts he already kept from the war. This little desk-ornament P-38 was carved, he told me, from aircraft aluminum scrap by some Chinese artisan. No doubt it wasn’t made for idle amusement, but to put a little food on the table. It’s a good job, and not demeaned by having been won at a poker game.

My dad did not actually set me on the road to modeling, but when I was very young, occasionally some friend or relative would give me a model kit. Of course at age 7 or so, it was way beyond my ability to assemble one, but Father would take an hour so with me in the evening to build it, and I would watch, and help put on the decals. (See the photo for the surviving example of his handiwork, and mine. To this day, I get a special thrill out of dipping those first decals in water, as the completed kit sits before me, awaiting its decorations.)

Then, as I've written in this column before, on my 11th birthday party I was given the Monogram kit of the B-58 Hustler, and borrowed my mother's small stock of Testor’s enamels, plus Father's No. 11 X-Acto knife, to commence my modeling career. Dad was supportive, back Then, even buying some of my kits. In my mature adulthood Now, after a long time in the ‘Dark Ages’, I resumed plastic kit modeling. From a modern discount department store, probably his nearby Fred Meyers, he made me presents of Testor’s Chance Vought F4U Corsair and Nieuport 17 kits. Closely examining them, I realized Dad had managed to give me—again—kits he’d originally bought for me back Then in the early '60s.

Like so many of his Generation—not mis-labeled as the ‘Greatest’—Father is gone from this world now. All the World War II vets are dying and will soon be gone.

I wish there were a way to thank them all for having won a great war, crossing all those humps…and beyond that, for having come back, established normal lives, and sired and provided for us Aging Baby Boomers. I’ve added to my tangible worldly treasures the book I gave to Father, along with his ‘ancient’ artifacts. I can’t count, weigh, or measure the intangibles I still owe him for. Help me imagine asking him—and all his veteran contemporaries—if their exertions and sacrifices were worth it, if only to make possible a world where their progeny could indulge in the hobby of modeling. Don’t you agree they would have laughed—but after a moment’s reflection, said "Yes!" I’m confident they would—and do—endorse our philosophy:

Build what you want, the way you want to…and above all, have fun!