Aurora 1/48 scale Messerschmitt Me-109 Kit No. 55By Tom Dobbins |

|

We have a guest columnist this month!

(Ed. note: Article revised & updated 6 June.)

“Sherman, set the Wayback Machine to 1960.”

“Right away, Mister Peabody.”

If that snippet of dialog triggers vivid memories of the Rocky and Bullwinkle

Show, chances are that you’re already familiar with Aurora’s

Messerschmitt Me-109. It is a rare modeler of my generation (I’m

rapidly approaching the half century mark) who didn’t build at least

one in their youth. Examples of this legendary “Famous Fighters”

kit appear every month or so on eBay, where pristine specimens often fetch

prices well in excess of $100.

The prolific 1960 issue of the Aurora Me-109 kit featured iconic box

art by Mort Künstler, whose paintings began to attract the attention

of serious art collectors a little more than a decade after his Aurora

Plastics Corporation commissions. (Still kicking, he has emerged as America’s

premier historical artist, focusing primarily on Civil War subjects.)

Although Künstler depicted an aircraft with a rounded spinner and

a large supercharger air intake under attack by a Spitfire, anyone expecting

to find a kit of the F or G variant inside is in for a rather nasty surprise.

I can still recall being utterly perplexed and bitterly disappointed as

a lad of six or seven by the failure of the model to even remotely resemble

the splendid box art. The tailplane bracing struts present on all of the

pre-F variants are absent, but the truncated conical spinner and squared-off

wingtips immediately rule out a machine of the F or G subtype. While the

prominent radiator bath on the fuselage chin is a hallmark of the early

B, C, and D variants, the three-bladed propeller, twin underwing radiators,

and shrouded exhaust manifolds all suggest the Me-109E.

Why such a hopeless muddle in a kit of an aircraft that was produced

in greater numbers than any other? The Aurora tooling was closely copied

from a solid wood kit of the Me-109 produced by the Dyna-Model Products

Company of Oyster Bay, New York that first appeared on the market in 1950.

The Dyna-Model plans were based on a set of notoriously inaccurate drawings

made by William A. Wylam in 1940 for Model Airplane News. The vertical

tailfin is woefully undersized as well as misshapen. The fuselage, equal

in length to the wingspan, is a whopping 12% too long! Even at a glance,

the assembled model looks as if it’s been stretched on a rack.

The initial 1953 issue was molded in vivid red, but the subsequent 1950s and 1960 issue kits were all molded in a deep metallic burgundy, with the exception of the 1965 issue of the kit (marketed in conjunction with Quinn-Martin’s popular “12 O’clock High” TV series on ABC), which was molded in olive green.) A dense peppering of saucer-sized rivets more appropriate

for a 19th century locomotive than a 20th century airplane was added to

the original tooling in 1954. My specimen has prominent sink marks on the cowling,

rudder, and landing gear doors.

The initial 1953 issue was molded in vivid red, but the subsequent 1950s and 1960 issue kits were all molded in a deep metallic burgundy, with the exception of the 1965 issue of the kit (marketed in conjunction with Quinn-Martin’s popular “12 O’clock High” TV series on ABC), which was molded in olive green.) A dense peppering of saucer-sized rivets more appropriate

for a 19th century locomotive than a 20th century airplane was added to

the original tooling in 1954. My specimen has prominent sink marks on the cowling,

rudder, and landing gear doors.

Even by the standards of 1960, Aurora’s Me-109 is so laughably

inaccurate and primitive that it is sure to reduce any modeler who suffers

angst about rivet count or the thickness of undercarriage doors to a quivering

mass of jelly. Spurious features include a narrow rectangular band with

a pebbled texture atop the left wing root, intended no doubt to represent

a wing walk. The control surfaces are only vaguely delineated by very

shallow recessed lines, the undersurfaces of the single-piece wings are

devoid of recessed wheel wells for the landing gear, and to add insult

to injury, the outlines of the wheel wells are indicated by not one but

two concentric rows of rivets!

Cockpit detail? There is no cockpit! The head and shoulders of a rather

crude pilot figure are molded into each half of the fuselage. Masking

the rather diffuse edges of the canopy frame is a daunting task.

Attaching the wings to the fuselage at anything even approaching the

proper dihedral angle requires using a file to either narrow the tabs

protruding from the wing roots or to widen the corresponding slots in

the fuselage. Otherwise the wings will actually droop slightly below the

horizontal! The holes on the undersides of the wings are too small to

accept the locating pins on the radiators and bombs. The fit of the remaining

parts leaves little to be desired, however.

The fuselage and wings contain raised outlines to guide decal placement.

I had long imagined that Aurora’s mold designers disdainfully regarded

modelers as too obtuse to properly locate decals without such features

until I perused a copy of a little Dell paperback published in 1961 entitled

The Complete Book of Plastic Model Kits. Compiled by the Advisory Board

of the Aurora Plastics Corporation, it contains the following passage:

While most figures, letters, numbers, and insignias are furnished with

the kits in the form of decals, some builders prefer to paint them as

they are outlined in the plastic. Insignia and letters or numbers may

be painted by using a small brush with all but 8 or 10 hairs removed.

Masking or cellulose tape may be used to cover any areas where paint is

not desired.

The

box art of the earliest issues of the Aurora Me-109 featured black swastikas

surrounded by white discs on the tailfins of garish red aircraft (and

misspelled “Messerschmitt” as Messershmitt” to boot!).

The raised outlines of the swastika were molded into the plastic as well

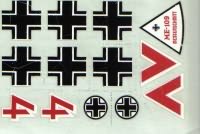

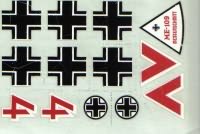

as printed on the decal sheet. In 1960 the swastika was replaced by a

fictional Balkan cross lest someone be offended by the symbol wielded

by Etruscans, Hittites, Hindus, Jainists, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, Native

Americans, Celts, Slavs, Balts, Finns, and various virulent German ultra-nationalists.

The discs were bisected by the vertical stabilizer and the rudder, the

location specified in prewar Luftwaffe paint schemes.

The

box art of the earliest issues of the Aurora Me-109 featured black swastikas

surrounded by white discs on the tailfins of garish red aircraft (and

misspelled “Messerschmitt” as Messershmitt” to boot!).

The raised outlines of the swastika were molded into the plastic as well

as printed on the decal sheet. In 1960 the swastika was replaced by a

fictional Balkan cross lest someone be offended by the symbol wielded

by Etruscans, Hittites, Hindus, Jainists, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, Native

Americans, Celts, Slavs, Balts, Finns, and various virulent German ultra-nationalists.

The discs were bisected by the vertical stabilizer and the rudder, the

location specified in prewar Luftwaffe paint schemes.

Other than the national insignia, the decals offer only a chevron and

the numeral “4,” both rendered in red with white borders,

signifying the fourth aircraft of Staffel flown by an adjutant belonging

to a squadron’s first Gruppe. In my specimen decal registration

is quite good except for the chevrons and numerals.

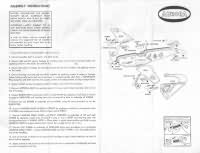

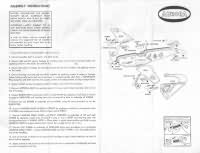

The

austere instructions include no reference to painting the model. In fact,

aside from an unobtrusive advertisement for Aurora’s glossy “Speed-Dry”

enamels, they give no indication that it was even intended to be painted.

On the contrary, after attaching the landing gear as the final step in

assembly the modeler is instructed to simply apply the decals. Kunstler’s

box art shows a pair of aircraft with yellow spinners and a fictional

color scheme

The

austere instructions include no reference to painting the model. In fact,

aside from an unobtrusive advertisement for Aurora’s glossy “Speed-Dry”

enamels, they give no indication that it was even intended to be painted.

On the contrary, after attaching the landing gear as the final step in

assembly the modeler is instructed to simply apply the decals. Kunstler’s

box art shows a pair of aircraft with yellow spinners and a fictional

color scheme  consisting

of dark mauve upper surfaces over sharply delineated light blue undersides.

Perhaps those are the most appropriate colors of lipstick to put on this

pig.

consisting

of dark mauve upper surfaces over sharply delineated light blue undersides.

Perhaps those are the most appropriate colors of lipstick to put on this

pig.

Like the aircraft it depicts, the Aurora Me-109 kit is now a piece of

history. Prized by collectors but sure to be despised by builders, at

best it can only yield a caricature rather than a replica.

The initial 1953 issue was molded in vivid red, but the subsequent 1950s and 1960 issue kits were all molded in a deep metallic burgundy, with the exception of the 1965 issue of the kit (marketed in conjunction with Quinn-Martin’s popular “12 O’clock High” TV series on ABC), which was molded in olive green.) A dense peppering of saucer-sized rivets more appropriate

for a 19th century locomotive than a 20th century airplane was added to

the original tooling in 1954. My specimen has prominent sink marks on the cowling,

rudder, and landing gear doors.

The initial 1953 issue was molded in vivid red, but the subsequent 1950s and 1960 issue kits were all molded in a deep metallic burgundy, with the exception of the 1965 issue of the kit (marketed in conjunction with Quinn-Martin’s popular “12 O’clock High” TV series on ABC), which was molded in olive green.) A dense peppering of saucer-sized rivets more appropriate

for a 19th century locomotive than a 20th century airplane was added to

the original tooling in 1954. My specimen has prominent sink marks on the cowling,

rudder, and landing gear doors.  The

box art of the earliest issues of the Aurora Me-109 featured black swastikas

surrounded by white discs on the tailfins of garish red aircraft (and

misspelled “Messerschmitt” as Messershmitt” to boot!).

The raised outlines of the swastika were molded into the plastic as well

as printed on the decal sheet. In 1960 the swastika was replaced by a

fictional Balkan cross lest someone be offended by the symbol wielded

by Etruscans, Hittites, Hindus, Jainists, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, Native

Americans, Celts, Slavs, Balts, Finns, and various virulent German ultra-nationalists.

The discs were bisected by the vertical stabilizer and the rudder, the

location specified in prewar Luftwaffe paint schemes.

The

box art of the earliest issues of the Aurora Me-109 featured black swastikas

surrounded by white discs on the tailfins of garish red aircraft (and

misspelled “Messerschmitt” as Messershmitt” to boot!).

The raised outlines of the swastika were molded into the plastic as well

as printed on the decal sheet. In 1960 the swastika was replaced by a

fictional Balkan cross lest someone be offended by the symbol wielded

by Etruscans, Hittites, Hindus, Jainists, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, Native

Americans, Celts, Slavs, Balts, Finns, and various virulent German ultra-nationalists.

The discs were bisected by the vertical stabilizer and the rudder, the

location specified in prewar Luftwaffe paint schemes.  The

austere instructions include no reference to painting the model. In fact,

aside from an unobtrusive advertisement for Aurora’s glossy “Speed-Dry”

enamels, they give no indication that it was even intended to be painted.

On the contrary, after attaching the landing gear as the final step in

assembly the modeler is instructed to simply apply the decals. Kunstler’s

box art shows a pair of aircraft with yellow spinners and a fictional

color scheme

The

austere instructions include no reference to painting the model. In fact,

aside from an unobtrusive advertisement for Aurora’s glossy “Speed-Dry”

enamels, they give no indication that it was even intended to be painted.

On the contrary, after attaching the landing gear as the final step in

assembly the modeler is instructed to simply apply the decals. Kunstler’s

box art shows a pair of aircraft with yellow spinners and a fictional

color scheme  consisting

of dark mauve upper surfaces over sharply delineated light blue undersides.

Perhaps those are the most appropriate colors of lipstick to put on this

pig.

consisting

of dark mauve upper surfaces over sharply delineated light blue undersides.

Perhaps those are the most appropriate colors of lipstick to put on this

pig.(Ed. note: Thanks, Tom!)